Understanding Private Equity

Private Equity

-

What is private equity?

Private equity is an asset class that includes companies that are not publicly listed on a stock exchange. A private equity investment typically involves the takeover of a company, which is then restructured as a limited partnership. Private equity can be divided into several categories including leveraged buyouts (LBOs), venture capital (VC) and distressed investments. The purpose is to unlock value from the target company that was not previously recognized in the marketplace.

-

How do private equity partnerships work?

Private equity is typically structured as a partnership with a general partner (GP) and limited partners (LP). The GP is responsible for sourcing, reviewing and executing investment opportunities as well as overseeing daily operations and decision-making of the fund. The GP prepares the legal framework, including the offering memorandum. The LPs are the individuals and institutional investors providing most of the capital. Once the partnership has reached its targeted size, it is closed to new investors and operates with a fixed amount of capital.

-

What role does private equity play in a portfolio?

Private equity, one of the oldest forms of investing, offers portfolio diversification, tax efficiency and potential for higher absolute returns over time than traditional investments through lower correlation. Private equity also carries different risks than traditional investments.

-

What is unique about private equity cash flows?

In the early years, investors typically experience negative cash flows as capital is called for deployment. As time goes by, the cash flows increase and turn positive. This is known as the J-curve effect. As the fund matures, cash is returned to investors through distributions generated from the return on the initial investment. On average, a private equity fund will hold an investment for three to five years prior to exiting. The holding period is dependent on various factors including economic and market conditions.

-

How liquid is private equity?

Investors should be aware of private equity’s long time horizon and lack of short-term liquidity. Traditional private equity partnerships typically last 10 to 15 years. Historically, it was difficult for investors to readily liquidate their private equity investments. However, over the past decade, there has been a growing secondary market for private equity. Secondary markets can provide added liquidity for existing investors. But that liquidity comes at a price as buyers typically purchase private equity interests at discounts to their net asset value or NAV.

-

What are the benefits of private equity?

dding private equity to a portfolio may enhance overall returns, provide greater diversification, improve tax efficiency and dampen volatility. Private equity ownership takes a more active approach to investing and often includes management or board representation. This structure provides greater influence on the strategic direction of the company as well as better alignment of interests between investors and management. Unlike publicly traded stocks, private equity funds are not priced daily so their price volatility and return correlation may be lower.

-

Who invests in private equity?

Investors in private equity include pension funds, endowments, foundations, high-net-worth individuals and other long-term investors. In the 1980s, institutions were the primary allocators to private equity funds. Today, while institutions still make up the majority of private equity investors, we’re seeing more high-net-worth individuals taking advantage of new structures offering lower minimums. HNW investors have grown more comfortable with illiquid assets as they view illiquidity as a necessary tradeoff for potentially higher returns and added diversification. Private equity investing often carries high investment minimums and, in some cases, may only be available to accredited investors with at least $1 million in assets.

-

How is private equity performance calculated?

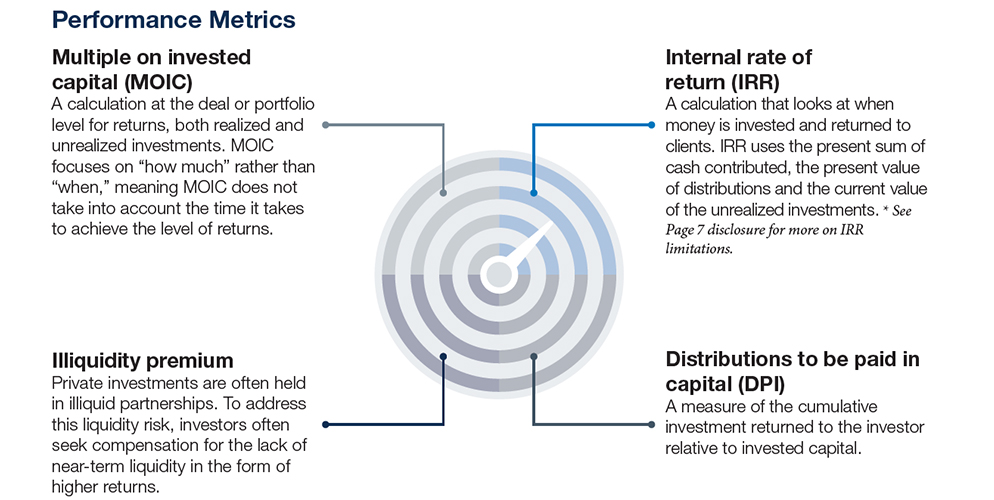

Two widely used methods are internal rate of return, or IRR, and multiple of invested capital, or MOIC. IRR is the discount rate that sets the net present value of a series of cash flows equal to zero. IRR allows investors to measure the performance of a series of irregular cash flows. MOIC is the calculation between capital invested and capital returned. For instance, $1 invested in a private equity fund that returns $5 in distributions implies a 5x multiple return. This feature is beneficial for investors, as capital is called and invested over time, resulting in negative cash flows, while distributions generate positive cash flows for the investor. MOIC is a measure of capital invested versus capital returned without any sensitivity to the timing of cash flows.

* See disclosure for more on limitations of IRR.

-

What is the difference between a primary fund and a co-investment?

Primary funds are commingled investments—money from different investors is pooled into one fund—that invest directly in private companies. Generally structured as closed-end funds, primary funds raise a fixed pool of capital from limited partners, which is then drawn down to fund investments. Investments are made at the discretion of the general partner who sources, conducts due diligence, executes and actively manages the portfolio. In primary funds, the investor does not know what’s inside the portfolio—a blind pool—as funds are raised first and invested in companies later.

A co-investment offers limited partners the ability to invest in private companies alongside the general partner. Given the greater transparency offered by the general partner to evaluate the investment, co-investments can help mitigate the blind pool risk often associated with primary funds. However, despite this mitigation investing in this manner is still riskier and more speculative than traditional investments such publicly traded stocks, bonds or cash.

What are the risks of private equity?

Given record deal flow and increasing investor capital flows, one of the biggest challenges facing private equity is the ability to put this flood of new capital to work. Defined as the amount of committed, but unallocated capital, “dry powder” is approximately $1.8 trillion. Competition to deploy this capital and higher multiples being paid to acquire companies has led to increases in valuations, which depending on market conditions at the time of exit, could have a negative or positive impact on performance.

Private equity investments tend to involve companies with speculative growth, less stable cash flows and do not have a publicly quoted price, so they may be riskier than publicly traded securities. Competition for discovering investment opportunities on attractive terms may be high. Capital withdrawal creates a likely increase in business and financial risks. Additionally, portfolio firms may find that subsequent rounds of financing are difficult to obtain. The portfolio firms’ products and services may be adversely affected by government regulation. Tax treatment of capital gains, dividends or limited partnerships may change over time. Valuation of private equity investments is subject to significant judgment. When an independent party does not conduct valuations; they may be subject to biases. Private equity is subject to changes in long-term interest rates, exchange rates, and other market risks, while short-term changes are typically not significant risk factors.

How can private equity achieve higher rates of return?

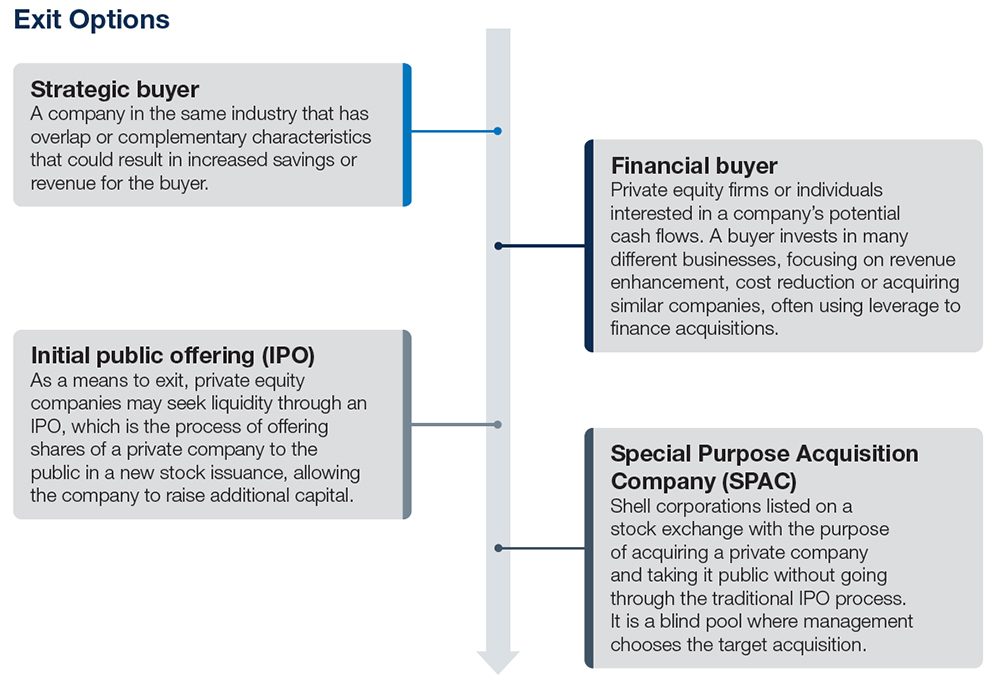

Private equity investing allows investors to invest at lower valuations than what would normally be available in the public market. As these investments mature, investors may be rewarded for the value created when it culminates through an IPO, a sale or a merger. Private equity investors typically demand a premium as compensation for giving up near-term liquidity. Private equity is also less correlated to traditional asset classes such as stocks and bonds.

How has the public market changed in recent years?

Over the last 10 years, the number of public companies has decreased significantly while private market assets have grown to $6.5 trillion. This is partly due to the different governance requirements between public and private ownership and the growth of private markets. In addition, businesses are staying private longer. During 1998-2000, the average age of 100 technology companies’ pre-IPO was approximately five years. Comparatively, for the 2018-2020 period, that age increased to 12 years. Today, 87% of U.S. companies generating more than $100 million in revenue are private companies.

Glossary

-

Blind pool

An investment in a primary fund without knowing its future investments. The fund will make investments that are in line with the fund’s investment mandate, with limited to no influence by the LPs.

-

Capital call

Notices issued to LPs when the GP has identified a new investment and a portion of the LPs’ committed capital is used to finance its operations.

-

Carried interest

The share of partnership profits received by the GP, with the remainder distributed to investors, regardless of whether the GP contributed any capital. It is essentially a performance-based fee that motivates the general partner.

-

Catch-up

Once a fund has returned all capital to investors and reached its desired return, the GP begins to collect carried interest dating back to the initial profits returned by the fund. To recoup their share of the proceeds, GPs often include a catch-up provision to retain most of the fund’s profits until it has received its share of the gains.

-

Co-investment

An opportunity to invest alongside a private investment fund, typically on a discretionary basis.

-

Committed capital

The money that an investor has agreed to contribute to a fund.

-

Distribution

The disbursement of assets from a fund, either in cash or shares.

-

Distribution waterfall

A method for prioritizing cash flows from a private equity investment among limited partners and the general partner. The waterfall includes a return of capital, preferred return, catch-up and carried interest. The purpose is to align incentives for the general partner and define payments for limited partners.

-

J-Curve

The direction of cash flows—in the shape of the letter J—through the life cycle of a private equity fund. In the early years, investors provide capital and pay management fees, which leads to negative cash flows. Over time, cash flows turn positive as returns on the initial investment are realized.

-

Limited partnership

The legal structure through which institutions and individuals invest in private equity, generally fixed-life partnerships.

-

Preferred returns

The targeted minimum annual return provided to limited partners before the general partner shares in profits. It ensures the general partner will share in the profits only if the investments meet or exceed the preferred return.

-

Schedule K-1

IRS documentation distributed to investors by a partnership, which provides flow-through income, losses and dividends reported on an investor’s individual tax return.

-

Vintage

A term used to describe the year in which a fund is formed and the initial drawdown of capital occurs. Vintage also refers to the year in which a partnership closes to new investors.

Private Equity is a type of alternative Investment. An alternative investment is a financial asset that does not fall into one of the conventional investment categories. Conventional categories include stocks, bonds, and cash.

Alternative investments are not appropriate for all investors and many may only be offered to certain qualified investors. Investors must be able to bear the economic risk of such an investment for an indefinite period and can afford to suffer the complete loss of investment. An Investor’s ability to redeem from such investments is limited to specific time periods (eg. monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, annually) with certain notice requirements.

Oppenheimer Asset Management is the name under which Oppenheimer Asset Management Inc. (OAM) does business. The Alternative Investments Group (AIG) is a division of OAM. OAM is a registered investment adviser and is an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Oppenheimer Holdings Inc., which also indirectly wholly owns Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., a registered investment adviser and broker dealer.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the managers and not necessarily those of Oppenheimer Asset Management Inc. and are subject to change without notice. Some of the alternative fund managers that OAM is recommending are recently formed and have limited operating history.

Some newly formed managers and funds may have limited assets under management. With newly formed managers, there may be greater operational and financial risk factors. Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. has selling agreements with the hedge funds on the alternative fund platform. Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. receives part of the management fee and incentive fee and does not receive the same compensation from each hedge fund. This may be a potential conflict of interest for Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. and its financial advisors to recommend funds that pay higher compensation.

There is a substantial risk of loss when investing in alternative investments and, for each specific fund, the risk of underperforming the general markets or other funds. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Indices are unmanaged, hypothetical portfolios of securities that are often used as a benchmark in evaluating the relative performance of a particular investment. An index should only be compared with a mandate that has a similar investment objective. An Index is not available for direct investment, and does not reflect any of the costs associated with buying and selling individual securities or management fees.

Private companies are generally not subject to SEC reporting requirements, are not required to maintain their accounting records in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, and are not required to maintain effective internal controls over financial reporting. Private companies may have limited financial resources, shorter operating histories, more asset concentration risk, narrower product lines and smaller market shares than larger businesses, which tend to render such private companies more vulnerable to competitors’ actions and market conditions, as well as general economic downturns. These companies generally have less predictable operating results, may from time to time be parties to litigation, may be engaged in rapidly changing businesses with products subject to a substantial risk of obsolescence, and may require substantial additional capital to support their operations, finance expansion or maintain their competitive position. These companies may have difficulty accessing the capital markets to meet future capital needs, which may limit their ability to grow or to repay their outstanding indebtedness upon maturity.

Some of the information in this document may contain projections or other forward looking statements regarding future geopolitical events or future financial performance of funds, countries, markets or companies. Actual events or results may differ materially.

A drawback of IRR calculations is their inherent assumption that investors will be able to reinvest any distributions from the investment at the IRR rate. In practice, it is unlikely that this would occur. Another drawback is that in order to calculate IRR for a portfolio that includes holdings that have not yet been sold (or otherwise liquidated or matured), a valuation of those remaining assets must be estimated. Depending on the nature of the asset, these estimated values may be based on subjective factors and assumptions.

Indices are unmanaged, hypothetical portfolios of securities that are often used as a benchmark in evaluating the relative performance of a particular investment. An index should only be compared with a mandate that has a similar investment objective. An index is not available for direct investment, and does not reflect any of the costs associated with buying and selling individual securities or management fees.

S&P 500 Index

The S&P 500 Index consists of 500 stocks chosen for market size, liquidity and industry group representation. It is a market value weighted index (stock price times number of shares outstanding) with each stock’s weight in the index proportionate to its market value. The index is one of the most widely used performance benchmarks for U.S. large-cap equities.

Cambridge Associates U.S. Private Equity Index

The Cambridge Associates U.S. Private Equity Index is an index based on quarterly performance data compiled from 1,486 US private equity funds (buyout, growth equity, private equity energy and mezzanine funds), including fully liquidated partnerships, formed between 1986 and 2018.

Russell 2000 Index

The Russell 2000 Index is a small-cap stock market index that makes up the smallest 2,000 stocks in the Russell 3000 Index.